Ethiopia’s capital Addis Ababa is one of the most dynamic and fastest growing cities in Africa. The city is the seat of the African Union’s headquarters, with a significant presence of foreign embassies and United Nations offices, it is considered to be the diplomatic capital of Africa. Addis Ababa is also the hub for Ethiopian Airlines, the largest airline in Africa, and is home to multiple local and international businesses. As such water supply needs to be stabilized not only for its year-round residents but also for seasonal visitors that call the city home anywhere from several weeks to many months. Addis Ababa is the economic epicenter of Ethiopia as it is reported to generate 29% of the country’s GDP and 20% of national urban employment. The city remains at the center of a socio-economic interdependence between the neighboring Oromia State and the Federal Government of Ethiopia. A significant number of people work in the city and live in the suburbs directly contributing to this mutually interdependent relationship. However, the city’s chronically unbalanced water supply and demand hardly keeps up with the current pace of population growth.

Over the recent years Addis Ababa’s population has increased by more than 4% year over year with the current estimated city’s population standing at about 5.2 million. This rate of growth is expected to continue with a significant gap in supply and demand for water, a problem expected to linger for the foreseeable future. If the current water demand was to be fully met, it would require an estimated supply quantity of 1.2 Million m3/day. This discrepancy is in stark contrast with the current water production rates from both surface water and groundwater estimated to be at an annual average of 0.48 Million m3/day, a coverage of only about 40% of the daily requirement!

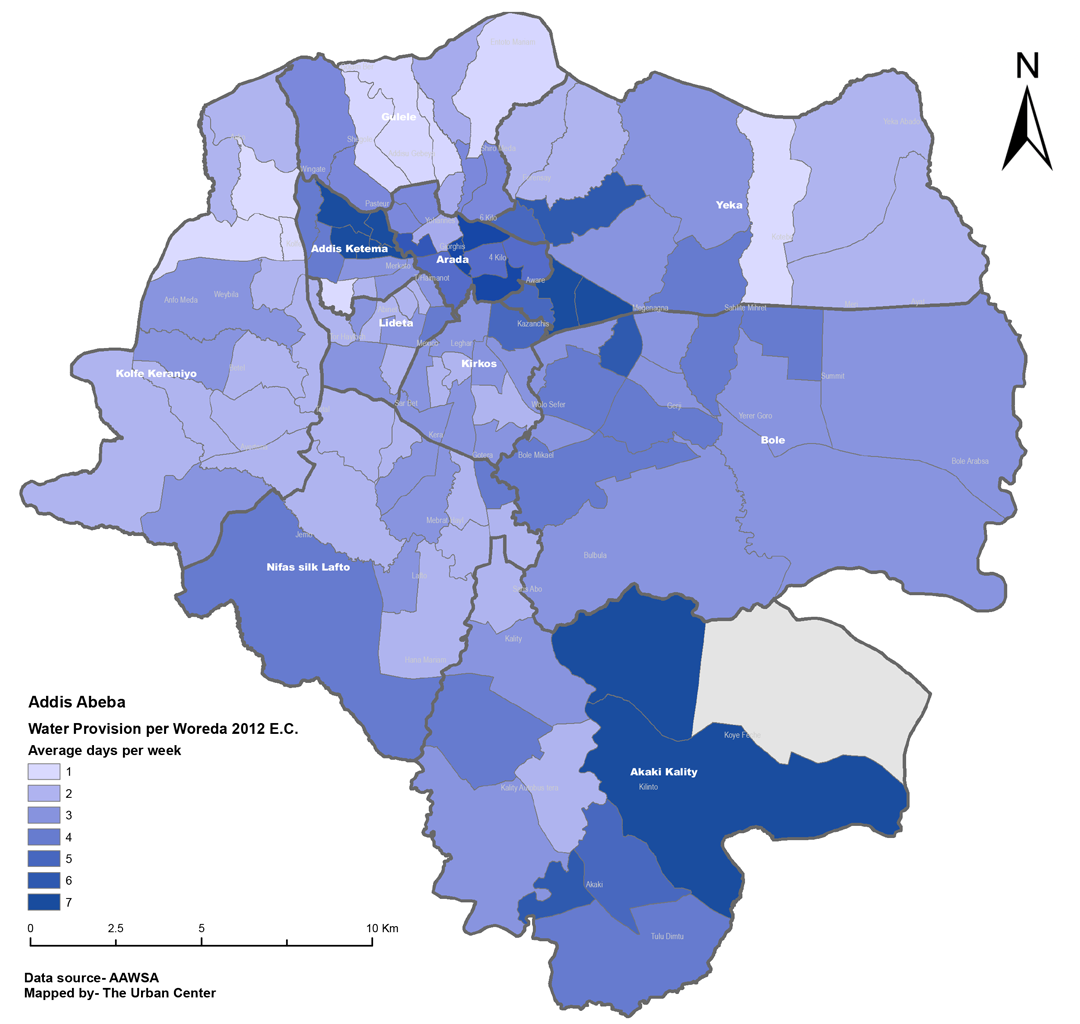

This significant imbalance between demand and supply is recognized by the Addis Ababa Water and Sewage Authority (AAWSA), the city’s major water and wastewater service provider. As such, a water rationing delivery plan has been put in place for some time. Large parts of the city get water rationed two to three days per week. Similarly, the central part of the city, which is the downtown area, gets water supply for four to six days per week. In addition, there is a considerable amount of pent-up demand from new building construction throughout the suburbs and surrounding areas. This new demand has yet to be accounted for and the systems need to be connected to the central AAWSA distribution network.

Figure 1: Regional water rationing schedule developed by AAWSA

The current and short-term urgent water requirement of several construction companies building homes and businesses that are in various stages of completion means the city will continue to experience the disruption of water supply service for the foreseeable future.

The Problem with an Intermittent Operating System

The lack of reliable service coverage means water delivery interruptions are widely evident and acknowledged by users who are looking for solutions. Residents face the challenges of dealing with chronic water supply shortages in their day to day lives. Unfortunately, Addis Ababa’s water supply system is not designed to operate intermittently. Water rationing, beyond supply challenge, is also a huge problem for longevity of existing infrastructure. Frequent water hammering, which is the sudden distribution pressure buildup because of changes in system related to forced interruptions, leads to a short lifespan of existing water supply infrastructure investment. Such practices also lead to frequent network breakdown and inflow of contaminants, endangering the sustainability of infrastructure and health of customers. There are dire consequences of such type of operational decisions including:

The inability of the system to maintain proper water quality parameter residuals (e.g. chlorine residuals) which might lead to unsafe water adding stress to the already burdened healthcare sector resulting in serious implications.

Wastewater systems could become inefficient and unable to handle blackwater. This stumbling block will force the city to spend more money than planned and pose potential health issues for the residents.

A significant impact on how existing businesses or new businesses who want to relocate to Addis Ababa and the surrounding areas use water. This could put undue pressure on the local trade and drag down the overall Ethiopian economy.

Frequent on-and-off operations puts the distribution systems under significant stress resulting in breakage thus increasing further non-revenue water loss which, in turn, limits the ability of AAWSA to perform important Renewal and Replacement (R&R) projects.

Coping Mechanisms by City Residents

A near 60% demand-supply gap means not all residents, even those with in-house connections, will have access to clean water at all times. AAWSA has instituted a water rationing plan where several sub-city administrative regions get one to two days of water supply per week. Those who get water only once in a week would have to pray that the distribution system near them doesn’t lose power on their designated days. If power interruption occurs on the designated water availability schedule, which is often the case, customers would have to wait for the following week, losing access to water for two weeks in a row. There are no makeup dates. This kind of interruption has pushed almost everyone who can afford it to install a water storage tanker on their premises. This is witnessed by the not so far away scenery from the skyscrapers of the business districts depicting an unflattering aerial view with hundreds of water tankers popping up every few days. On-premise installations of 1,000 to 10,000 liter tankers are considered to be the current solution and many residents have already taken that route. Typically, these on-premise water storage tankers only allow a selected number of residents to cope with the intermittent water supply issues they are facing. Unfortunately on-premise storages do not increase the city’s total water supply. Instead they simply shift the water use to those who can afford to build larger tankers on site and store large quantities of water between rationing schedules, furthering the inequality of access to water in the city. This, in turn, results in an increase in the frequency of interruptions for the same limited resource. This fact is supported by the AAWSA data that shows a staggering 20% of accounts utilizing 80% of the volume of water supplied. There is an alarming water use profile inequality currently being witnessed in Addis Ababa!

In this neighborhood in Addis Ababa, almost all houses have tankers installed on their rooftops. The ability to install tankers is considered a luxury.

The chronic water shortage in the city has also created a booming parallel “water trading” market in the last few years. Small scale businesses have flourished by buying water at point of origin prices from AAWSA from one part of the city during the rations and selling to other users on the other side of the city at a higher price, thus making a profit. The cheap price of piped water charged by AAWSA (compared to other cities in developing countries of similar size), has inadvertently created and enabled a duplicate water trucking business for some individuals. In turn, AAWSA finds itself undermining its own revenue streams that could have been collected and used to fix these issues.

The water trucker companies serve both individual consumers (e.g who have to buy Jerry Cans of water and carry them into multi-story buildings for toilet flushing) as well as booming business construction sites in the periphery of the city. While the total demand-supply gap still remains the same, this parallel market simply reallocates the existing supply amount tilting the balance to those who can afford to pay more than the price of water charged by AAWSA. Many residents recognize this and often say they would prefer to pay more to AAWSA for a more reliable service than rely on the street water trading which is astronomically expensive and of questionable quality. It’s therefore not surprising that almost everyone in Addis Ababa uses bottled water for drinking. In addition, there are private businesses that supplement their piped AWWSA water with “their own” local groundwater which receives a significant markup and is eventually sold to other parts of the city.

Unregulated Groundwater Extraction

In the absence of a reliable and adequate water supply, businesses and affluent residents are looking to their own solution by tapping groundwater. One of the cardinal sins of unsustainable water mismanagement of groundwater sources is excessive abstraction. Groundwater is replenished by deep aquifer recharge that seasonal rainfall provides. Typically, groundwater levels get low towards the end of the dry season and get replenished at the end of the rainy season when excess rainfall finds its way into the deep aquifers. The speed with which rainwater finds its way to deep aquifers and the amount of groundwater replenishment depends on several factors including the amount of water that makes it deep into the earth as well as how porous, (or not) the overlying successive stratified geologic formations are. This water movement may take from a few months to decades depending on climate and hydrogeologic conditions. These factors have implications on how sustainable a given level of groundwater abstraction is.

If more people are digging into the ground to tap into groundwater and this activity exceeds the rate where groundwater can be replenished (the natural recharge) in a reasonable amount of time, groundwater wells will risk becoming dry. There is evidence to suggest that in Addis Ababa this is a common phenomenon: water wells becoming dry after a few years of completion. Recent data in a wellfield in the city of Akaki, for example, shows observed significant yield reductions in several groundwater wells based on data from 2017 through 2019 supplied by the Ethiopian Construction Design and Supervision Works Corporation. Overall, wellfield level yield reductions have been attributed to several factors. Of this, 75% are attributed to pump failure, 12% unconnected boreholes, 8% pumps with reduced discharge, and 5% yield decline because of water level decline. The solution adopted for dry wells is to go to another place a few miles away and dig a deeper well, which would operate for a few years. Only for some of these wells to go dry in a few years of operation. We have seen video taped evidence of initial well exploration hit a significant artesian aquifer where water flows freely to the surface after the immediate operational periods. Without a robust monitoring system and a regional groundwater quantity assessment in place, identifying well pumpage interferences and quantifying sustainable recharge quantities may not be feasible.

Then the cycle repeats.

Groundwater well exploration depth around Addis Ababa has been increasingly deeper as the rate of extraction far exceeds that of the replenishment rate. The problem is worsened by unaccounted for well extractions which are dug into the same aquifer. This development results in regionally lower groundwater level, which in turn requires digging deeper. Today, most wells are hundreds of meters (equivalent to few football fields) depths below ground surface.

As part of “firefighting” the current increased demand-supply gap, authorities at AAWSA are strongly encouraging businesses to look for local groundwater by themselves as the city water distribution becomes increasingly limited in its coverage. The city has insufficient resources available to cope with higher demand and this is adding pressure on the current operations. The scope and magnitude of current operations, maintenance, and management of non-revenue water, let alone new supply expansion appear overwhelming to AAWSA. In addition, expanding existing water distribution networks in already congested city easements is proving to be a challenge. Furthermore, Addis Ababa’s unforgiving city topography exacerbates the problem of getting clean water as many places as it needs to be.

In fact, a simple web search for a new business such as those in mixed-use planned developments highlights this new “trend” of real estate business advertising. Several luxury real estate developers at the heart of the city advertise their “independent and uninterrupted” additional groundwater supply to woo potential buyers. Most of these businesses are hooked to the city distribution network but also have their own groundwater sources to cope with the interruption. Between “their own” local groundwater, few tankers and rationed AAWSA supply, these businesses can afford to promise potential buyers that they have successfully overcome the water supply issue in their properties that customers see everywhere else.

Considering that water supply and power supply in Addis Ababa are unstable, internal water and power supply systems are specially set in house, namely, well and power generation equipment are self-equipped to guarantee 24/7 power supply to enhance your life quality in an all-round way

-Ad taken from a popular real estate business in Addis Ababa.

The Dangers of Unmonitored Groundwater Usage

Pump, and pump, and pump some more. . .

As far as we are aware, there is limited knowledge of how much water is being currently extracted outside of the wells that are owned and operated by AAWSA. Regional monitoring and evaluation of the groundwater resources and current production are severely lacking. Also limited is research on the overall availability of groundwater in and around Addis Ababa and its characterization. Inadequately characterized is also the recharge area (supplying water for these wells to continue pumping) to the deep aquifer that sustains major groundwater sources around Addis Ababa. Some put the recharge area beyond the vicinity of the city and perhaps to other interconnected basins.

All of these issues need to be verified and addressed.

Whatever the extent of the recharge area and sustainable quantity, current abstraction rates appear to be more than the rate of groundwater replenishment as evidenced by frequent drying of wells. Our experience shows that properly operated and maintained pumps and motors should last twenty to thirty years. This is not the case in places we visited.

In addition, while the practice of only sourcing groundwater appears to be an attractive and cost effective method to bridge the significant demand-supply gap, it is not sustainable in the long term. Solving Addis Ababa’s chronic water shortage would require multiple and diversified solutions including addressing the problem of non-revenue water and loss, implementing proper pricing and utilizing additional surface water supply with a potential inter-basin transfer.

Regional scale water resources assessment used to characterize the quantity and extent of groundwater resource and monitoring and regulations on water use is nowhere to be seen in Addis Ababa and surrounding regions. The lack of a comprehensive approach makes it difficult for effective resources management. Everyone is putting their “straw” in the same aquifer with no knowledge and documentation of how many of these “straws” even exist and how much water is being currently taken out and how safely the current extraction rate could be sustained into the future. This unaccounted, uncoordinated, and unmonitored withdrawal is a disaster waiting to happen. These businesses that are “guaranteeing” their “own” groundwater may run into an issue in a few years time. When there is no comprehensive groundwater regulation and a well thought out monitoring program, it could make today’s problems more difficult to resolve a few years down the road.

Implications for Addis Ababa’s and Ethiopia’s Economy

Addis Ababa’s fast growing population, the large number of businesses present impacts the country’s standing making the city a high powered economic engine for Ethiopia. Lack of dependable access to water supply will be a huge challenge to the city and its surrounding development. Addis Ababa’s competitiveness as an international hub for businesses and industries could be seriously challenged. Access to clean water and sanitation is a huge factor in the decision of businesses to locate in a growing city like Addis Ababa that aspires to be at the center of booming businesses in sub-Saharan countries. Today, there are several other cities in Africa not far from Addis Ababa that are competing for those same businesses. Therefore, time is of the essence for coordinated solutions to address this chronic water supply shortage. Collaboration among the city, the Federal Government, and Oromia State is urgently needed now.

What can we do about it?

There are many examples of cities overcoming chronic water supply issues in their growth trajectories around the world such as the South-North water diversion project in China at a larger scale or Quito, Ecuador at a smaller scale. In addition to the experiences of other countries, we recognize that there are several positive on-going experiences of handling mega projects in Ethiopia and political willingness to address the problem. In our follow up article, we will provide additional insights on what can be done to tackle this problem. In the meantime the Addis Ababa water time bomb keeps ticking.

Dr. Tirusew Asefa

Dr. Tirusew is the lead for decision support group at Tampa Bay Water, the largest wholesale water supplier in the Southeastern US. He oversees agency work on surface and groundwater resources assessment, supply planning, demand forecast and management, and climate adaptation among other responsibilities. Tirusew is a registered professional engineer with the State of Florida, a Diplomate of the American Academy of Water Resources Engineers, and a Fellow of the American Society of Civil Engineers. He currently chairs Florida Water and Climate Alliance. He can be reached at mululove[at]yahoo.com

Dr. Fekadu Moreda

Dr. Fekadu Moreda is Senior Water Resources Engineer at Research Triangle Institute International. His expertise in hydrology and hydraulic engineering includes building hydrodynamic models, implementing models for flood forecasting, lead water resource assessments, and training water resource managers. Currently, he leads the development and implementation of the Hydrology and Climate for Latin America and Caribbean (Hydro-BID) water resources management simulation system. He can be reached at fmoreda[at]rti.org